Barbados-based photographer Mark King recently spent two weeks in June as an artist-in-residence at the Alice Yard space, Woodbrook, Port-of-Spain Trinidad. “I came to Trinidad with the birth of an idea,†says King. The residency opportunity was King’s first visit to the island. His photographic project would be based on his outsider knowledge of the place. According to King: “For many years people have told me how exotic and beautiful Trini women are. It often dominated the conversation when men discussed the island. This was hard to ignore and led me to embrace the subject and do a project exploring this perception of Trini women. Then I was going through some things I had and found a book on the birds of Trinidad and Tobago by Richard ffrench and thought I would relate the birds to Trini women. There are a variety of women in Trinidad and that has to do with hybridisation and creolisation. Trinidad is a very multi-layered place.â€

Barbados-based photographer Mark King recently spent two weeks in June as an artist-in-residence at the Alice Yard space, Woodbrook, Port-of-Spain Trinidad. “I came to Trinidad with the birth of an idea,†says King. The residency opportunity was King’s first visit to the island. His photographic project would be based on his outsider knowledge of the place. According to King: “For many years people have told me how exotic and beautiful Trini women are. It often dominated the conversation when men discussed the island. This was hard to ignore and led me to embrace the subject and do a project exploring this perception of Trini women. Then I was going through some things I had and found a book on the birds of Trinidad and Tobago by Richard ffrench and thought I would relate the birds to Trini women. There are a variety of women in Trinidad and that has to do with hybridisation and creolisation. Trinidad is a very multi-layered place.â€

A surface reading of the connection King makes between women and birds may yield a feeling of offense and a hasty condemnation of his work but King’s project lends a powerful, nuanced appreciation of the socio-cultural constructions of gender and the dynamics of the interface between men and women. Bird watching or birding has long been a male-dominated practice of observing feathered creatures in their various habitats for aesthetic value. Bound up in the aesthetic principle underlying acts of watching is an inclination toward classifying and sorting birds. Psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen calls this a process of “systemizing.†Bird watching is not however, restricted to the birds in a literal sense. Bird watching as a metaphor has, for some time, seeped into interactions between men and women. The word “bird†is a colloquial term used among men in places like the UK and Trinidad to refer to women. The “bird watching†practice in this sense also involves a systemising process in which women are ranked and categorised. Trini women usually fall into a dominant mental category. The Trinidad habitat is known in popular opinion for its women classed as having beautiful physical attributes. In his article entitled “Female Facts,†author Kevin Baldeosingh speaks of Trinidad’s “high proportion of nice women.†Yet, Baldeosingh – himself a Trinidadian – does his own further classification. “I don’t like Trini women just because of their physical attributes: I also like them because a lot of our women are what I call ‘femaleists’ – i.e. independent in spirit but not edgy about it and, unlike a certain brand of feminist, preserving a genuine affection for men (undeserving though we might be),†says Baldeosingh, who insists that serious investigations into Trini women can provide “fundamental insights†to the workings of Trinidadian society. Baldeosingh maintains that research into and scrutiny of Trini women is his “obligation as a writer.†For photographer Mark King, his stay in Trinidad allowed him to do his own watching and study of Trini women, aided by his camera.

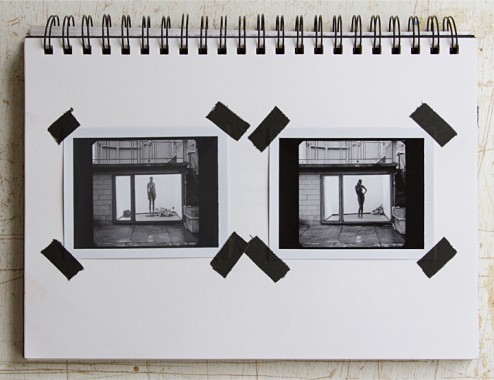

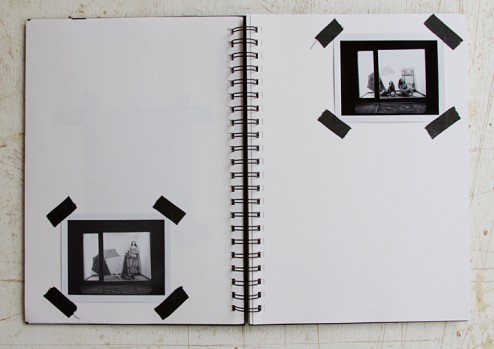

King arrived in Trinidad and immediately began to acquaint himself with the place and the people. “Feeling out a place informs my work. I do people-based work influenced by my surroundings,†notes King. He became acutely aware of Trini women from what he describes as different groups (although these groups could overlap): “natural beauty,†“office/corporate women,†“party/club women,†“athletic/fitness women†and “Amazonian women.†A visit to Trinidad’s National Museum also informed and developed his idea. Seeing taxidermied birds in glass boxes with accompanying details of their scientific classifications was a catalyst for King’s consideration of glass settings or “windows functioning like nests where the female is prominent,†King explains. The use of a glass environment for female subjects would be appropriate for describing the personal, micro context of King as an outsider looking in. It could also serve as a comment about a macro socio-cultural milieu of “bird watching,†in other words, as a reflection on a broader context in which men watch and systemise women as specimen. “A diorama would make sense,†says King, who quickly got to work, building sets within Alice Yard’s glass-enclosed exhibition space. Desks, flowers, sand and beach umbrellas are among the elements used to create such habitats as office settings and beach locations. “The beach scene in particular,†notes King, “is fitting to the fantasy†of the tropical, Trini woman. King then staged and photographed women in these various settings.

Among his photographs are images of Trini women in “the nude†– to use King’s words here. King’s choice of the word “nude†instead of “naked†is noteworthy. “Nude†is a highly political term, in other words, one caught up in tensions of power. Nude is a convention derived from traditions within art history. English art critic and author, John Berger understands the term “nude†as a category or classification that can be distinguished from the term “naked.†According to Berger:

“To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become nude. Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display. To be naked is to be without disguise. To be on display is to have the surface of one’s own skin, the hairs of one’s own body, turned into a disguise…. The nude is condemned to never being naked. Nudity is a form of dress.â€

King’s work can be seen as offering a display of women in the “dress†of nudity, yet by portraying the women in a standing position as opposed to a supine one, he straddles the line between objectification and a presentation of these women as erect agents of their own image, where they are active subjects of their bold nakedness. His nude images are also reminiscent of a Gauguin-esque portrayal of tropical women. French artist Paul Gauguin’s depictions of Tahitian women have received much scholarly attention, including feminist enquiry. Feminist analysis has furnished the argument that Gauguin’s art has played an instrumental role in the establishment of a trope in which tropical women are always seen as exotic. However, reading King’s work in relation to Gauguin allows us to not only see King’s nudes as inscribed with the category of exoticism but to also consider his renderings of bodies coded with what Jane Duran argues is a sacred sensuality – a “transcendental sacredness,†where the body moves beyond the limits of a physical classification; beyond the simplistic and reductive confines of an object.

King’s project is very much about a taxonomy of women. He does not subvert the male gaze but rather, he amplifies and reinforces it in such a way that calls it into sharp scrutiny. His use of photography for this project not only recalls the key place visual devices like cameras, binoculars and telescopes have held in traditional bird watching practice but it also opens up space for a critical conversation about a socio-cultural optics, that is, about the kinds of lenses through which we see, give focus to and interpret women. His is vital work, which has the potential to inform relationships between men and woman and shed further light on issues of visuality, identity formation and the construction of people as emblems of place. While his residency at Alice Yard has come to an end (an experience which he describes as an incredible one), he is hopeful that he can return to Trinidad to do further photographic explorations of Trini women. He aims to continue creative movements away from what he describes as “the literal.†It would be fascinating to see this work in progress, develop to the extent that it engages at a level of complexity that considers how women watch and construct themselves. Again, we may turn to the work of John Berger as a useful resource for thinking along this line. In the book Ways of Seeing, Berger observes: “A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually.â€

To follow Mark King’s work visit: www.markkingismarkings.com

via — link