via gaurdian Shortly before taking the Long Island Rail Road out to spend the day with Italian conceptual artist Vanessa Beecroft, I eat a huge American-style breakfast at the Empire Diner in Chelsea – two fried eggs, potato chips, English muffin, two slices of toast – and end up with stomach ache. This over-fuelling stems from the knowledge that Beecroft, now 35, has struggled to control an obsession with food since the age of 12. Bearing this in mind, it’s unlikely she’ll be offering me anything to eat. My hunch proves correct. When I arrive at the scenic, coastal home that Beecroft shares with her husband Greg Durkin, 28, a social researcher, and their two sons (Dean, three, and Virgil, seven months) her British assistant, Ian Davis, mutters knowingly: ‘I hope you had breakfast today.’

Everything in Vanessa Beecroft’s life revolves around food. She and her husband bought their rural retreat in Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, partly because it would cut Beecroft’s access to the 24-hour convenience stores available on every street corner in New York City – too much of a temptation when the craving for a binge comes on. They also bought it because it had an indoor swimming pool.

Beecroft suffers from what psychiatrists call ‘exercise bulimia’, a compulsive need to burn off unwanted calories using excessive exercise. For Beecroft, swimming was, until recently, an intoxicating drug. When she was pregnant with Dean, she insisted – despite the protests of her husband and his mother, Sheril Durkin, a registered dietician – on swimming 100 laps a day to ensure her weight gain was kept to the minimum. Today, she no longer swims, instead practising ashtanga yoga (‘power yoga’) seven days a week. Without it, she says she would ‘go crazy’. In her teens, she tried unsuccessfully to vomit food she wished she hadn’t eaten – all that saved her from rampant bulimia was her body’s refusal to play ball. The spectre of anorexia haunted her teens and twenties, too, when she smoked to keep her weight down, attempted crash-dieting with amphetamines, undertook damaging fasts, exercised beyond any sensible limits of endurance, and kept a diary – The Book of Food – detailing every single morsel that passed her lips between 1983 and 1993 (for example, if she ate an orange, she’d note the date, time and how it made her feel). Even now, a decade after she stopped keeping the food diary, there are still days when she longs to note what she eats, such was the power of this coping mechanism.

Beecroft announced herself boldly to the art world in 1993, when she showed The Book of Food. After a professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera Scenografia in Milan, where she studied from 1988 to 1993, invited her to participate in a group show at the city’s Inga-Pin gallery, she adapted what remained of The Book of Food (the first four years of entries were lost by a friend hired to type them up) into a white cube-shaped book. The book, placed in the centre of an empty gallery, was supplemented by a ‘live sculpture’ or ‘live painting’ of 30 girls, consisting of fellow Brera students or girls found on the streets of Milan, who were instructed to move around the space, aloof, numb, dressed in Beecroft’s own clothes – mostly red or yellow (two of Beecroft’s favourite colours). Many of the girls, chosen for their uncanny resemblance to Beecroft, were themselves struggling with eating disorders. On the walls, drawings and watercolours of girls wrestling with eating disorders, primitive brightly coloured stick figures (sometimes just an arm or a torso or hair or a leg) reminiscent of sketches by Tracey Emin (all chronologically titled VBDW01, VBDW02, VBDW03, the acronym standing for ‘Vanessa Beecroft Drawings and Watercolours’).

This first ‘performance’ set the blueprint for Beecroft’s future as a conceptual artist. Since then, she has staged a further 53 performances around the world (all titled VB01, VB02, VB25, VB45, etc), each more elaborate than its predecessor.

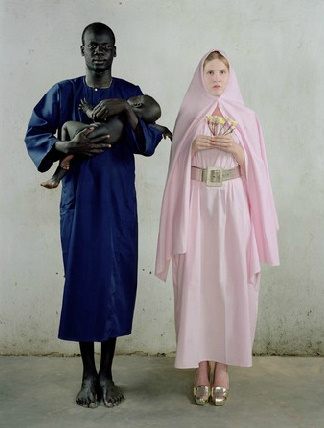

Earlier performances tended to feature a handful of girls wearing high heels (Beecroft calls heels ‘pedestals’), cheap costumes and wardrobe, allusions to European cinema (films by Fassbinder, Godard, Visconti) and classical painting (Rembrandt, Holbein, della Francesca), and red, yellow or platinum wigs. As budgets grew in proportion to her reputation, she started using professional models, strikingly presented by make-up artists such as Pat McGrath, and wearing clothes and accessories loaned or specially created by fashion designers such as Miuccia Prada, Tom Ford, Helmut Lang, Dolce & Gabbana, and Manolo Blahnik, all eager to associate themselves with Beecroft’s complex vision (even if Beecroft’s assistant tells me ‘The fashion in Vanessa’s work is a red herring’ and Beecroft herself says, ‘I don’t follow fashion’).

Many of these mutually beneficial artist/designer collaborations (Beecroft gets kudos from the fashion press, the designers get intellectual cachet from the art press) are brokered by Beecroft’s long-term friend/mentor Franca Sozzani, the influential editor of Vogue Italia, who sees a very clear role for fashion in Beecroft’s work.

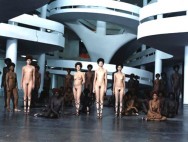

‘Fashion is important in her performances because she subdues it to her will,’ Sozzani tells me. ‘It’s not important as a logo, trend or status symbol: fashion items are used to underline the woman’s body and to express the concept behind her performances.’ The ‘girls’ (Beecroft’s term for the models) have also become increasingly stripped, to the extent where most performances since VB23 have featured partial or full nudity. These beautiful and disturbing tableaux vivants, which are always staged twice (once for the public, once for photographing and filming: Beecroft’s network of dealers trade in limited-edition photographs and DVD/video films of each performance) have confounded critics eager for easy categorisation, been pronounced ‘dope’ by celebrity fans such as Leonardo DiCaprio, been slated as vapid art/fashion fusion catwalk shows, and enraged older generations of feminists while thrilling the younger. As Maria Elena Buszek, an art historian at the Kansas City Art Institute, explains: ‘Beecroft is the veritable poster-girl for our current, third wave of feminist art history. There’s an ambivalence in her work that is present in the work of many of her contemporaries, which is the result of a culture that has both internalised feminist goals more than any generation that preceded it, and chafes against what it perceives as feminism’s restraints.’

On 8 April, at the Neue National galerie in Berlin, she will stage her biggest performance to date, VB55, featuring 100 girls. The resulting three prints and solitary DVD are expected to set a new record for sales of Vanessa Beecroft’s art.

Arriving at Beecroft’s house, my taxi driver clocks the silver BMW in the garage, the indoor swimming pool and the sprawling countryside surrounding the house, shakes his head and says, ‘Damn, these motherfuckers got it all.’ At the door, I’m greeted by one of two full-time nannies, a smiley Virgil in her arms.

In the living room, I find Beecroft sitting on a white-leather couch, talking with her assistant. As she introduces herself in a lilting Italian accent, I note her healthy weight, the toned, muscular ashtanga arms, her big eyes – at once little-girl vulnerable and tomboyishly tough.

It transpires that, in a moment, she is heading outside to pose naked for the photographer and his assistant, the four inches of snow that fell overnight making for a beautiful backdrop. ‘I’m letting society take revenge,’ she says, alluding to critics who hone in on her willingness to put naked women on display, while never – with one or two exceptions – appearing in the performances herself.

She tells me she hates being photographed. ‘When I am photographed, in my face and in my eyes there is too much heaviness. I look at a camera and all the heaviness comes. But the girls, they’re pure.’ The girls (with the notable exception of VB39 and VB41, both of which featured male members of the US Navy as ‘models’, her performances always consist of female models) are self-portraits according to Beecroft, diary entries translated to a safely distant, removed canvas of space and anonymous flesh. She assigns the girls – who vary in look from heavy to plain to model-beautiful to tattooed to pierced to unhealthily thin – her shame, her self-disgust, her anxieties. She turns the girls, some of whom have been diagnosed with eating disorders, into a reflection of her own ugly emotional panorama.

Art magazine Parkett has also noted that there’s a ‘cruel classicism’ to her aesthetic: she makes the girls stand for up to three hours in uncomfortable high heels, sometimes several sizes too small; she has had the models’ pubic hair shaved to make their public violation more complete; and she gives them strict rules (don’t talk, don’t move, don’t make eye contact with the audience). It’s no wonder that Fassbinder, a master of cruelty and control, is one of her favourite film directors (Fassbinder actresses Irm Hermann and Hanna Schygulla were cast as ‘characters’ for VB51 in Germany).

After 54 performances, many remain unsure what to make of Beecroft’s work. Some see the fashion element as superficial, some see the naked Helmut Newton-esque images of these women as little more than ‘hooters for intellectuals’ (as one review famously dubbed her work). Some say she’s demeaning women, parading them like hunks of meat, in the process creating a male wet dream, while others say she’s reclaiming sexualised images of women from the pages of Penthouse and recontextualising them as symbols of feminist empowerment.

Laura Piccinini, a journalist for Italian women’s monthly Amica, told me that Beecroft’s eating disorders, her obsession with fashion, her deliberately provocative use of nudity, make her a perfect tabloid-friendly artist for our confessional, celebrity-gossip and reality-TV-obsessed times. Beecroft’s art is one of exposure.

‘I had a difficult childhood,’ says Beecroft, still shivering from the photo shoot, as she warms her hands on a mug of Yogi Tea. We’re sitting at the dining table, a whole shelf of Helmut Newton books behind her (when Newton photographed her wearing a leather bikini for Vogue, he screamed at her: ‘I am the father of your performances!’). She was born in Genoa, Italy, on 25 April 1969, to a British father, Andrew (a teacher, then classic-car dealer, today retired and living in Beckenham with his second wife and their two children), and an Italian mother, Maria Luisa (a classics teacher, also retired, who lives alone in Rapallo). Her parents chose the name Vanessa after seeing Vanessa Redgrave in Antonioni’s Blow-Up while Maria Luisa was pregnant.

Straight after Vanessa was born, the Beecrofts moved to Holland Park, west London. When she was three, her parents separated (Beecroft would not see her father again until she was 15) and her younger brother (currently training to be a judge in Italy) was sent to live with Maria Luisa’s parents in Genoa. (‘As of today, I still ask my mother why and she says she couldn’t take care of two children,’ Beecroft says.)

Vanessa and her mother moved to a tiny village, Malcesine, on the slopes of Lake Garda. There, her mother taught at a local school and kept an austere house which included a strict macrobiotic diet. Running an atheist, manless home, working full-time and subscribing to far-left political ideals hardly endeared Maria Luisa to her fiercely Catholic, family-centric neighbours.

They called the Beecrofts ‘the foreigners’, treating them with suspicion. Today, Beecroft is proud of her mother, though, calling her a ‘progressive feminist’.

‘It was a very strange and primitive state of living,’ she explains. ‘No phone, no TV, no car, no meat. My mother was against modern society. She was angry about everything – men, the Pope, religion, meat. But she was not a hippy at all because she was a well raised Italian woman.’

Her earliest memories are of running through fields with boys and drawing pictures of her dolls. When she was 11, her mother moved them to Santa Margherita, a seaside town just along the Ligurian coast from Portofino, so Vanessa could re-establish contact with her brother (their father was in London and she wouldn’t see him again until she was 16, when he dismissed her from his doorstep for being ‘too intense’).

‘People were more spoiled,’ she says. ‘When we arrived, I was wearing wooden shoes and they laughed at me. That was difficult. But at school, I was good at drawing. I saw a way of escaping in art, so I decided to focus on studying.’

Her problems with food started with puberty. ‘When I was 12, I started to become a woman and my body began to change. I was devastated because I couldn’t be a boy any more. I lost my boyish look. When I started to become something else, I didn’t know how to keep it together. It was really painful – the more you eat, the more like a woman you become. That’s when my obsession with food started. I felt very alone, but now I see that every woman in my family has an eating disorder.’ At 14, she went to art school in Genoa. In her spare time, she read Vogue (her mother wouldn’t let her read it at home), visited galleries across Italy with her mother and spent weekends with her best friends – three aristocratic, anorexic sisters. She also started The Book of Food. ‘The anxiety of having eaten something and having it inside and not knowing how big and how much… I thought, “I’m going to write it down and look at it and see if it’s really so much. And one day, I might give it to a doctor so they will analyse if it’s OK.” But then it became an obsession and I wrote down everything I ate. I would go all day thinking, “I ate an apple at 12 o’clock, I must write it down, I mustn’t forget.”‘

Alongside food entries, she added comments like: ‘I am a pig’, ‘Slut’, ‘Terrible anxiety’, ‘Dogged bulimia’, ‘I’m bursting’, ‘Apathy fear fatigue’, ‘Trying to vomit’, ‘Monster’. As The Book of Food attests, things got worse. One day, in a fit of despair, she ate a whole bag of walnuts, shells and all, and had to be rushed into hospital and treated for peritonitis. ‘The doctor said, “What are you eating?”,’ Beecroft says, with a sigh. ‘I told him I was eating walnuts, the whole thing, with the shell. I was smashing them with a hammer and swallowing the whole thing. I thought it would be purifying.’ The doctor referred her to a psychiatrist. ‘He was a Red Brigade,’ Beecroft recalls, laughing. ‘I loved seeing him. But I had to leave because we couldn’t afford it. Instead I started to smoke cigarettes so I would become skinny.’

When she was 18, she enrolled at Genoa’s Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti Pittura, where, to Beecroft’s frustration, she was unable to make herself throw up, unlike some girls there. ‘Every other girl could and I couldn’t. I would try in the bathroom with my head in the toilet for two hours and eventually I’d start bleeding because I was hurting myself and I got scared. My best friend there used to be obese, and then she looked like a model because she smoked cigarettes all day and threw up, and I was so jealous.’ Unhappy, she transferred to the Brera Academy in Milan, supporting herself by working as a live-in au pair. Accepting that she couldn’t throw up her food, she started excessively exercising when the family was out (‘I would stay in my room and jump by myself and write down: 30 minutes jumping, 50 minutes jumping, in The Book of Food’) and began colour-coding her diet (a trick usually used by bulimics so they can identify specific foods when they vomit that Beecroft re-appropriated in a bid to turn herself into one of her own sickly stick drawings).

‘I thought that if I eat green, I will become green. So, for a long time, I ate only green food. And then orange food. And I was looking to my skin to become more green if I ate spinach, or orange if I ate carrots. I was trying to colour myself like in my drawings. I wanted my skin to be transparent, and the colours underneath orange and green and red.’ When she showed The Book of Food at Inga-Pin Gallery, she closed the diary: ‘The day I decided to use The Book of Food as art was the day I stopped.’

Instead, now able to afford gym membership, she binged on exercise – mostly aerobics and swimming. The exercise brought relief and offered an antidote to her problems. ‘Instead of this food,’ she explains, ‘instead of vomiting or doing what these other girls were doing, if I exercised, life was still worth living. I could go back to real life. Because as soon as food would come in, I would start to feel guilty, that I didn’t deserve to eat. Why should I eat? What should I eat? And the only way to deal with this was to exercise.’

Beecroft’s big break, the one that catapulted her on to an international platform, came in 1995, when influential New York art dealer Jeffrey Deitch saw a photograph from VB09 in an art magazine. ‘I saw a tiny image of her work which was presented at a gallery in Germany,’ says Deitch. ‘The image was just so arresting, because it was a new kind of reality that she had developed. It was not a painting or a sculpture, it was not a normal photograph, it was not just people sitting there in real life. It was something in between. It was like nothing I had ever seen before.’

Intrigued, he invited Beecroft to stage a performance in January 1996 to open his new second gallery, Deitch Projects. The result confirmed in Deitch’s mind that here was an entirely new artist at work.

‘Her work comes out very much from the tradition of Italian painting and sculpture – Italian Mannerist painting, Baroque painting, sculptors like Canova – and the tradition of performance art: Duchamp, Yves Klein, Gilbert and George. The foundations are classical Italian tradition and the tradition of radical performance art and live art. And then she’s also very much involved in something more contemporary, this world of reality TV and fashion shows. There’s an awareness of contemporary culture that’s in the mix as well.’

He became her dealer and Beecroft moved from Milan to Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Nine years later, Deitch has made a very tidy sum from selling Beecroft’s work to ‘collectors of great works of pop, minimal and conceptual art’, and sees her as spearheading a new wave of women’s art.

‘Vanessa’s a new kind of woman artist,’ he explains. ‘Without question Vanessa is a feminist, but she’s a very contemporary kind of feminist. There’s a new group of women artists and Vanessa’s in the vanguard, and I would also add Cecily Brown and Pipilotti Rist, where the women are using sexual imagery from a very powerful, very feminine point of view, and it’s a kind of powerful sexual imagery that can even intimidate the male. If one is present at a Vanessa Beecroft performance, they are not erotic. You feel the power of the women’s presence. It is an intimidating image.’

After marrying Greg Durkin in Portofino in September 2000 (the wedding was turned into a special project entitled VBGD – the couple’s initials), Beecroft spent most of 2001 pregnant.

‘I’m on Zoloft [an antidepressant], the only drug you can take when you nurse, a very little dosage, very small,’ she explains, rubbing her heavily tattooed arms. ‘It makes you numb, I kind of like it actually. But when I am not, oh my God. I stopped when I got pregnant with Dean and I got crazy again – the police arrived one night because I was breaking the car.’

This wasn’t the only time her husband Greg called the police during this era. The second time was in autumn 2001 when the couple got into another ferocious fight, at a hotel in Los Angeles. Beecroft was handcuffed by LAPD officers and only released when she calmed down. Once she had given birth to Dean, her psychiatrist put her back on Zoloft.

‘I take it to keep the family in peace,’ she whispers, as if telling me a secret.

‘I have to become numb or otherwise I become too much. I was raised by my mother throwing plates everywhere – tomatoes, plates – and everything was destroyed and then she’d cry a little bit and then it would stop. I thought it was normal to destroy the house. So I take Zoloft for the children, but also to survive. I am so high maintenance!’

We are interrupted by Dean, who joins us, doe-eyed, wanting to blow out the candle flickering on the table between us. It’s getting dark. I tell her I should get going. ‘Do you have anything to eat on the train?’ she wants to know. When I say no, she hurries to the kitchen and starts to make me a picnic. On the train, heading back to Manhattan, hungry, I open the plastic bag and find inside two apples, two sachets of Yogi Tea, peanuts, each carefully, individually wrapped.

As I bite into a green apple, I try to make sense of all the contradictions surrounding Beecroft: she’s a doting mother with a nine-to-five husband who calls herself a feminist; she considers her performances self-portraits but rarely appears in them herself; she is supported by powerful fashion figures yet claims not to follow fashion; she’s plagued by eating disorders but doesn’t care to label herself bulimic or anorexic; she’s obsessed with control yet surrounded by powerful people; she’s very much an artist of the moment but isn’t interested in any contemporary art after the abstract expressionists; she’s happy to put naked women on public display but finds being photographed herself agonising.

Her work is no less contradictory and that’s why she is so successful, so on the pulse. It’s the perfect product of a time when we claim to despise reality TV but secretly watch it; fear globalisation but cherish that Starbucks latte; see the vapidity of fashion but save up for a Prada jacket; bemoan our celebrity-fixated culture while tuning in to see that exclusive Madonna interview. As a culture right now, we’re a mass of contradictions and, like all great art, Vanessa Beecroft’s performances beam that uncomfortable truth right back at us.

{ 2 } Comments

We have a client who is interested in buying Vanessa Beecroft’s work. We have tried contacting her gallery in Italy. Do you know of a way we can reach her directly in the U.S.? Any information would be greatly appreciated.

Sincerely,

Julie Kolka

I don’t have any specific information, here is her website — vanessabeecroft.com