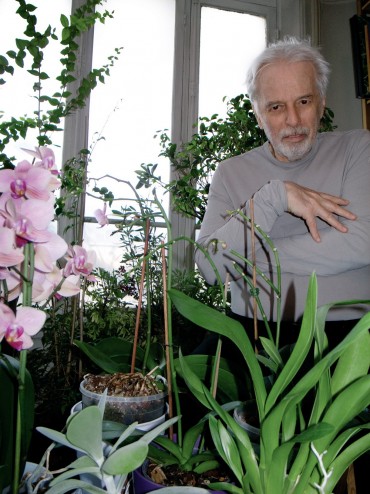

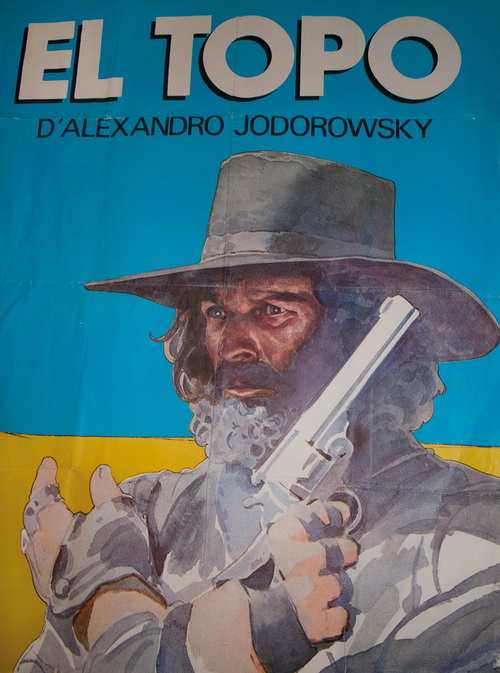

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY is best known for directing the cult movies El Topo, 1972, and The Holy Mountain, 1973. But he’s also a prolific writer, artist, playwright, philosopher, as well as a healer and magician — adept at every artistic activity, from the most abstract to the most popular. His passionate investigation of the Tarot coincided with the therapeutic session he calls PSYCHOMAGIC. A man of culture, at the crux of South American and European traditions, art is for him a form of rebellion, medicine, and spirituality which transcends all barriers.

photographs and interview by OLIVIER ZAHM

OLIVIER ZAHM — One thing that fascinates me about you is the world of symbols that cross your universe, your body of work.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — I was raised by a father who was a Communist and a Stalinist. He came to Chile from Russia when he was five. He wanted to be like Stalin. He dressed like Stalin. When I was four he said to me, “God doesn’t exist. You’re going to die, you’ll rot away, and that’s it.†He created a terrible neurosis in me, so I started life searching for truth.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Through the denial of God?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, and the idea that there’s nothing else. I was in total despair and didn’t accept this truth. I sought another truth through experience. I felt that through words I wasn’t getting anywhere, because behind every word was another word, and another, to infinity.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was this some kind of spiritual research through words?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Philosophy is a search for truth, but it isn’t the Truth. I wanted things to affect me concretely. The meaning of words didn’t have an effect on me, only their vibration did. Their beauty, poetry, and splendor impressed me. Through words I could receive beauty, but not truth. I didn’t want to say that truth was beauty. I was searching for things that affected me directly: symbols. A symbol doesn’t communicate a precise thing. It acts like a mirror and in that mirror you see what you are bearing, what you are. If you are able to see symbols, you’ll see yourself, and you’ll be able to control your progress, because as time passes and you develop, symbols change with you and accompany you.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Do you remember the first symbol or the first symbolic things you encountered?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, the Coca-Cola logo. I had a teacher, Oscar Ichazo, who was part of a movement called Arica. When I was in Mexico doing The Holy Mountain, we paid $17,000 for him to come for one night. I wanted him to enlighten me, to tell me the word, and he gave me LSD. He sat me in a meditation position in front of a luminous circle on a terrace. It was a spinning Coca-Cola logo. As it spun, it became a line, then a circle, and then the Coca-Cola logo, which I stared at for six hours. It was the Coca-Cola circle, a ring of light in the city, on top of a roof. And that’s when I had a flash of inspiration, a tremendous mental change.

OLIVIER ZAHM — The drug accelerated it?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It accelerated things I had never experienced but needed to know. To come to something, you have to know it. If you don’t know something, how can you look for it? From that moment on I saw that symbols enter into me. You don’t see them from the outside, like when you look at a fashion magazine. They penetrate into you like a key, opening inner dimensions, opening me up to things that are difficult to explain with words. Your being changes.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And enters into another dimension of consciousness?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It enters your dreams and changes them. I started having lucid dreams. One day I dreamt that I was leaving the planet. I was entering infinite space. I saw pyramids, a white one and a black one that overlapped to become one volume, a six-pointed star, but dimensional. I said to myself, “That’s divinity. I’m going inside.†I went inside and I exploded. When I woke up, I wrote El Incal, which I made with Moebius [the French comic strip artist, Jean Giraud]. It’s about the incorporation of symbols within yourself. El Incal talks about how the Incal enters into you and changes you. How an ordinary guy becomes the universe’s savior.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are you saying that you have led your life according to this interpretation and fascination with symbols? Do you think it’s a language that’s disappearing or that it’s not as powerful today?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — What the masses think doesn’t interest me, nor whether symbols are dying out or not. Esoteric teaching pays no attention to public thought. In working with symbols, I work with myself. My father told me I was an empty sarcophagus, that I would rot away, so I said to myself: “Being a prisoner of this body can be a wonder or a catastrophe. We all have incredible knowledge, but because there is death, there’s knowledge that we don’t have.†My life’s work has been discovering the knowledge within me. Where I perceive intuition, I develop it. You have to develop telepathy. You have to begin to develop what you are, but not from the point of view of an egomaniac or a narcissist. Words are transpersonal; they exist outside the artificial ego, which is put in our heads when we’re children. I write poems every day. Today I wrote, “Everything that is an owner, everything that has an owner, is not real.†I don’t want to be dependent on ideas or feelings or desires.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Are symbols a way to know and to liberate yourself?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Of course. When you speak of liberation, you enter into Buddhism, which is the philosophy of the great liberation. But Buddhism’s great liberation isn’t enough for me. It means to become free and to reincarnate, to be liberated from this life of suffering. I think the greatest liberation is to accept that this life is joy and to enter into it, living it to the fullest possible extent. We will perhaps pass on to another life, but that’s not where the interest lies. The interest lies in living in a state of bliss here and now.

PSYCHOMAGIC

OLIVIER ZAHM — Does the symbolic world also involve magic thinking?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, that’s why I invented Psychomagic. Magic is in beliefs, in superstitions; it seeks to dominate the outside world with rituals and symbols. Psychomagic is the control of the internal world, of a world outside of all superstition, and of all self-deception. I am mortal, but how can I think that I’m powerful when there’s this enormous universe of eternity and infinity? What right do I have to talk about such power? My power is that of knowing myself. On the façades of Greek temples was written the phrase, “Know thyself.†One can’t know anything more than that. Reality is not what it was, it’s not what it will be, it’s not what you want it to be. It is what it is. There isn’t anything nonessential about it, just things as they are. When we enter into what things are, we are in magic.

OLIVIER ZAHM — This symbolic world has been put aside. Symbols aren’t taught. We’re losing the sense of their importance.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — People want to have fun. So we give them entertainment, industrial cinema, television, internet. I address people who need to do work on themselves, and show them to what point I’ve come, to serve as an example of where they can go. Maybe they’re farther along than I am, perhaps not as far. In my films, I insert symbols for these people.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Have you been influenced by Castañeda?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — I liked his first three or four books. It was a cultural shock, because he admired something that was despised: Mexican Indian culture. Art must use what is despised as creative material. Not what is despicable but what is despised. That’s why I did comic strips, and why I did a cowboy movie, things that are rarely exploited in an artistic way. Castañeda had wonderful ideas, but he went from ritualistic, symbolic art — something true to himself — to whimsy in order to publish books.

OLIVIER ZAHM — He had the reputation of being very secretive.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, he was, but he was an icon because he succeeded in the United States. He was one of the first to bring shamanistic traditions to universities and anthropology. Later, he fell into guru madness. He had seen my film, El Topo, which was the underground film of the time. One day I was in an Argentinian restaurant in Mexico City, and a lady came over to me and asked, “Do you want to meet Castañeda?†He came to my table. We talked and set a time to meet again in a hotel, the Camino Real, where we talked and talked. Hollywood had made him an offer to make a film of his book, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. He’d made seven million dollars, and wanted me to direct it with Anthony Quinn in the role of Don Juan. I said to him, “That’s crazy. Who’s going to believe Anthony Quinn as Don Juan? It would be fun, but not true to the book.†So I said no. He’s smart, and understood that it would be a mistake. I understand that when Hollywood makes an offer to make a movie, some people can be tempted. Lets go back to Psychomagic. Is it a form of free psychoanalysis? — Yes, shamanistic psychoanalysis.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What’s your notion of Psychomagic?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It’s an art; it’s not a science. It has nothing to do with scientific therapy. But I’ve healed many more people than any psychoanalyst has. I’ve made people happy. What is it to be happy? It’s very simple: it’s being what we are and not what others want us to be. I am what I am. I live as I feel. I search for myself in order to know who I am and I don’t act to satisfy my father, my mother, my family, my society, or my culture. I escaped from that, and I fulfilled myself. The best example of this is Joseph Campbell, who wrote The Hero with a Thousand Faces. He’s a major expert of mythology, one of the top American anthropologists. He read mythology and abandoned everything. He left his family and went into the woods to read. He lived doing odd jobs. Then, after seven years, once he’d read everything he needed to, he took an exam at a university and he was immediately appointed professor. He became what he was and discovered happiness.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Does that mean you have to reach for your own limits?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. What do I want? What am I? Even your name and your definitions are artificial. You have to go beyond the definitions your family, society, and your culture have given you. This doesn’t mean breaking away from them. It means a metamorphosis, an expansion of consciousness.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You also explored the idea of a genealogical tree.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Psychogenealogy. Humankind cannot not be a family. Humans are influenced by the past and the past is transmitted by the family. We are shaped by the forest, which is society and transmits time, history, the past, and culture.

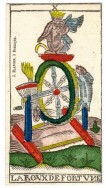

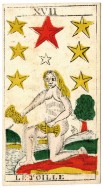

THE TAROT OF MARSEILLE

OLIVIER ZAHM — How did you work on this research?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — For seven years I went to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. I studied everything. I thought it was a system of symbols that I was supposed to learn. But the purpose of the Tarot is reading it for others. It’s not a personal thing. I read this sentence by Buddha, “I don’t want anything for myself that isn’t for others. Man’s goal is to change the world. If he cannot change it, he contributes to its change.†So I stopped reading the future, because that’s the defective and commercial version of the Tarot. There are thousands of possible futures, so I refuse to read the future. I also refuse to give advice, because it’s a way of taking power. The alternative is to offer options: if you do this, then there will be this result. If you do the opposite, then this. Also, I don’t think we can have the whole truth. At the end of the reading, I ask the person if they agree with the interpretation. I made huge progress this way, and my intuition has developed a lot. I did Tarot readings for 30 years in a café, once a week, every Wednesday. Except when I was sick or tired. People asked me when I’d be there and came without me having to advertise. I did Psychomagic and Tarot for free.

OLIVIER ZAHM — This world of Tarot symbols comes from several traditions.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It comes from every tradition. It’s a wonderful instrument because you find everything in it. Who could have built such an instrument? That’s the mystery. It was so advanced for its time. The first Tarot cards that we’ve found date back to around 1300. All kinds of origins are attributed to it: Arabic, Aztec, Jewish, Christian — everything’s there. In truth, Tarot is anonymous because it’s a sacred art, and all sacred arts are anonymous. It comes from dreams and the collective unconscious.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I heard that you made your own Tarot.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — A descendent of the Camoin family came to see me. That family printed Tarot decks for two or three centuries. The father of the boy who came to see me was run over, when the boy was 13. The family sold the business and the printing press, and offered the cards to museums, to collectors. This boy was deeply affected by it all. He was sad. I said to him, “You’re deeply affected, but really what you want is to continue your tradition. You are a master of cards. Salvage your tradition.†I spoke with his mother. The family gave us access to the museum and to the original printing plates. As a result, we revived the Tarot of Marseille. We went back to 1400. There’s not a single Tarot we didn’t find. At that time, Tarot cards were made by hand, painted by hand, and the backside was white and people used them like calling cards.

OLIVIER ZAHM — You were able to reassemble all 78 cards?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. Each Tarot deck has it’s own certain details. We looked for the hand-painted colors because when it came time to print them, the number of colors was reduced from 13 to four. If you compare an ordinary deck of Tarot of Marseille with a restored deck, you’d be shocked at all the details that have disappeared over time. For example, on the Hermit card there’s a blue hand. You might wonder why. The High Priest also has a blue hand. That’s something Camoin and I saw together. He saw incredible things because he was genetically a master of cards. On the High Priest’s blue gloves, there’s a little cross. The Hermit’s blue has a religious dimension; it’s the Pope who abandoned the Vatican and who withdrew from power. So, right away, the interpretation changes with the secret it gives you.

OLIVIER ZAHM — And you think this is the oldest Tarot?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, it’s the oldest. All the others aren’t worth much because they’re simple, almost rational interpretations of the Tarot of Marseille. They don’t have the small details. Because sometimes there are three little dots somewhere or a small circle. They’re full of details that we don’t see at first. We think it’s a primitive deck, or defective, but it’s not at all. Because on top of it all, there’s a geometric grid. You can place one card on top of another. They all have the same geometric configuration. There are about 8,000 Tarots. Every old adventurer thinks he’s made one. Seventy-eight Argentinian painters got together and made a Tarot they call the Argentinian Tarot. It’s tasteless. Such a lack of understanding! When I saw one, I said, “Pardon me for saying this to you. I’m not insulting you, but you don’t know what you’re doing. The Tarot cannot be Argentinian

— it doesn’t have a nationality; it’s anonymous.â€

OLIVIER ZAHM — So then why do we call it Tarot of Marseille?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Simply because the cards were printed in Marseille. The presses were in old places where the Knights of Templar were. Marseille was one of the only cities in France in the year 1000 where there were three very powerful religions that spoke to each other: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. They shared knowledge. The Tarot is the result of all that.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Tell me why the Tarot is so magical.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — The Tarot develops your intuition because it teaches you to see. There’s a rule of magic that says, “There, where you focus your attention, is where the miracle appears.†So it is very important to see the details in things. It’s a magical position par excellence. And the Tarot forces you to see such details. At first, you might understand the Major Arcana better because there are figures, but when you enter into the Minor Arcana, you see swords, staves, cups, and you don’t understand a thing. But after years of study you start to understand what they’re saying and learn to read the symbols.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But can’t everyone read them in their own way?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, it’s an art that combines the subjectivity of the reader and the subjectivity of the person being consulted. That’s why I always ask the person whose cards I’m reading if he agrees, and if it resonates. If it doesn’t, I offer him another interpretation, because people have defenses. We are who we are because we’re not able to face the pain we hide inside of us, that we bury. We want the pain to be taken away, but without being told why, without knowing what’s causing the suffering.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s better than taking antidepressants.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It’s a magic and metaphysical aspirin. The Tarot is subjective because, little by little, we go forward with the person as far as that person can go, but always with the person’s consent. You can never force people to face truths they can’t handle. Little by little, when they want to know things, we will go there.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Can it happen in one session?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, I do it in one session. It’ll have an effect immediately, or in four years.

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s followed by an action?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. For example, a woman came to consult me because her mother had an infection in her arm and no one was able to heal her. She asked, “What do I do?†I looked at the cards and saw that her mother had a deep bond with the great-grandmother. The mother felt guilt about her own mother. So I advised that her mother go to her mother’s grave, and to put honey on her arm, rubbing it in at the grave site and asking for forgiveness. It’s what she did and she was miraculously cured. When it’s psychological, you can take action. I don’t act on things that are a matter for medicine. I’m not a charlatan. I act on things that are only and deeply psychological.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Where medicine isn’t so effective.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. I’ve just written a book, Le Manuel de Psychomagie, that will come out in France, in which I offer advice for a series of problems.

SPIRITUAL COWBOY

OLIVIER ZAHM — In the films you made around the time of El Topo, there is always a relationship between a father and a son.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. Remember that at that time there was Pinochet, who was like a Hitler or a Mussolini. These dreadful father figures led societies. Then there were the uncles like the French president François Mitterand and Jacques Chirac. Now there’s a brother at the head of French Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy, who is neither an uncle nor a father. He’s a guy like you and me who has a filthy mouth, who functions like everybody, who’s proud to say, “My wife is a model.†We no longer have the anxiety of being dominated by a father.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was the motivation at the time to kill the father?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. I set out to kill the father in El Topo — he gets castrated — and in the end to absorb him. You feel sorry for the guy. He begins to become aware and, at the end, he works with his own son. The son can’t kill him, so he absorbs him.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There’s a very beautiful scene in which the son has to bury the portrait of his mother and his first toy. Killing the father, at the time, meant liberating oneself. Did it also mean to do so through drugs and sexual liberation?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — No, no, don’t mix up the terms. I have nothing against sexual liberation or against drugs, but I’m against the abuse of drugs, and I’m against the abuse of sexual liberation. All politicians should be advised to take hallucinogenic mushrooms once in their lives to open their mental state. In all the shamanistic religions, there’s a phase with drugs. It isn’t about the drug, but the ceremonial aid. I’m not against that at all. And I’m not against sexual liberation, but I’m against the abuse and disrespect of the sacredness of sex, because then it becomes an industry. So killing the father means killing Freud, killing Oedipus, who killed his father. So I start with that. I start with the vision that society has of killing the father, the clash of generations. But, after that, consciousness develops — consciousness about the other, about humanity. At that moment, the situation reverses itself, and there’s an absorption of the father, and of the values of the past, leading to a better future. Killing the father prevents us from moving forward. It means we are fighting against the past. America doesn’t believe in the past and therefore has become the most dreadful country in the world.

OLIVIER ZAHM — From that point of view, America is also the most infantile of countries.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes.

OLIVIER ZAHM — But to embody this trajectory of killing the father and then absorbing him, you use the figure of the spiritual cowboy.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — A spiritual cowboy who is led to develop his consciousness through suffering. Through enormous emotional pain, he’s destroyed, and then he recovers.

OLIVIER ZAHM — There are also several of those kinds of characters in The Holy Mountain.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — At the time, people didn’t know the enneagram. It was a symbol that Gurdjieff brought here, a symbol that comes from the Sufi group. It’s a circle with nine points, with a triangle inside, and a line. It’s a kind of “typology.†We are in a circle of planets. So I made an enneagram. There are nine characters with the master’s tent in the middle. The master in The Holy Mountain — a film based on the enneagram — has the enneagram sign on his chest. At the time, no one understood what I was talking about. Now Gestalt therapists use it. Claudio Naranjo is an important psychoanalyst who uses the enneagram. He divides his patients into nine groups and speaks to them about The Holy Mountain and asks that they see it. The enneagram symbolizes the planet as its opposite. For example, Mars, who is a man, becomes a lesbian woman, and Venus is a narcissistic man. Each is responsible for an aspect of mankind — laziness, pride, and so on.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I read that John Lennon wanted you to make the film.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes. He loved El Topo and he said to me, “You have to do what you want.†But I didn’t have money, so he said to me, “We’re going to talk with our producer Allen Klein and ask that he give you a million dollars.†I left with a million dollars and I made the film, thanks to John Lennon and Yoko Ono. They found me the money overnight.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Why did you stop doing fims for a long time after The Holy Mountain?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — The producer Allen Klein was angry with me. He wanted me to use the success of El Topo and The Holy Mountain to make the Story of O. I didn’t want to do an erotic film at the time. I wanted to do Dune. We were signing a contract for $300,000, but I left the check and I escaped. He said, “Okay, you don’t want to do this film? No one will ever see your other films again!†And he kept them. Then one day I found a good copy of the negatives in a Mexican lab. I called an English film pirate and said to him, “Listen, I’m giving this to you for free. Make it public!†He said, “But Allen Klein will come after me.†That’s why I did it. It was David and Goliath. There was a trial, of course, but I wasn’t looking for money. I didn’t want anything. I only wanted my films to be seen. Overnight I had an audience and I made a profit. So I saved money and stored it away to make a documentary on Psychomagic. Therapeutic cinema. Other projects came to me immediately. I waged a guerilla war. These bootlegs have been traveling across the world over for 30 years.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That must be how they became cult, underground films, as only certain artists were able to see them. Did you meet Sam Peckinpah?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — No, but El Topo was made with everything Sam Peckinpah left behind in Mexico. He made The Wild Bunch in Mexico. Americans have money. When he wanted to film a small mountain, he said, “Clear the way until here.†If he wanted horses, he said, “Bring me horses.†If he wanted explosions, a Mexican Indian taught him about explosions. After he left I found the Mexicans who taught him to explode things, the horse trainers, and the stuntmen. I found them all, and took advantage of them.

OLIVIER ZAHM — I’m surprised to hear than Peckinpah was more widely distributed than you were.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Of course he was! He was a Hollywood director and he worked in the movie industry. But what killed him was alcoholism. He went raving mad. He had his success, but he also had a negative vision of humanity, terribly cynical. I didn’t want that. I wanted the opposite. It’s easier to make a horrid, cynical film than it is to make a film that talks about mankind in a noble way.

OLIVIER ZAHM — What is your next film project?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — It’s crazy. I’m involved with four different projects, including King Shot with David Lynch!

OLIVIER ZAHM — It’s funny, because he directed Dune, a film which you wanted to shoot, but never did.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, but Lynch suffered a lot when he did Dune too. It wasn’t his fault. It was the producer’s fault.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Does Lynch like your films?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — He likes my films and I like his. We like each other a lot. When we met, we fell into each other’s arms. After that project, there’s The Children of El Topo, which is a Russian-American co-production, but will be titled Abel and Cain. Then I have Bouncer, the adaptation of my book, which was illustrated by François Boucq. It’s a classic western, which we want to produce in Spain. And there’s a Mexican who wants to produce Juan Solo. Soon we’ll see which one I’ll be doing — it’ll be the first one I get the money for. Stars participate as soon as they think you’re financially viable. But they want to act for me. First, I have the Pyschomagic documentary, which I’ll start filming at the end of the year. I’m going to make it with real people, a digital camera, and sound, and that’s all. You’ll see how crazy Psychomagic is. It’s wild but useful surrealism — theater taken to its furthest extent.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Besides your films, how do you put Psychomagic into practice?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — I’ve invented what’s called Social Psychomagic, collective acts to heal events that have affected a life or a country, like the slaughter of 2,000 students in Mexico. Or the healing of Guernica or Hiroshima. Suffering should be erased with a positive act.

OLIVIER ZAHM — That’s a very good idea. I went to Nagasaki and everything is set up so that people forget. There’s the museum, but you still feel like the past has been erased.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — The Japanese have chased out all the people affected by the atomic bomb, as if it’s a national disgrace. They don’t want to see them anymore, which is tragic. I’m going to make this movie and if I live long enough, I’ll do the four films.

LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT

OLIVIER ZAHM — The last things I want to talk about are women, love, and sexuality.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — You want me to call my wife, Pascale, who’s 40 years younger than me? You know, now, at 80 years old, I’ve found my ideal woman. I don’t come from love; my mother never touched me. In a certain way, she had contempt for me because my father raped her. I’m the second child. She told me, “After you were born, I got my tubes tied so I wouldn’t have any more of that bastard’s children.†So, I never knew maternal love. I talk about that in my books. I grew up in a man’s world, with masculine values, with a total lack of knowledge of women. I thought of women as peripherals who always wanted to chop off my head. A peripheral is always competitive. A peripheral always wants what the man has. So I went from one Vietnam War to the next, until I ended up with a Eurasian with Vietnamese roots! And that’s when I began to understand that women are slaves in this world. It’s a terrible thing, the way religion, the economy, and society keep them out or make them play a terrible role. There are a few women who fight it, but many partake in it, like women who wear a chador. I wasn’t finding the woman I was in harmony with spiritually. There was always doubt and effort. I made an effort to adapt myself. I never had an obvious encounter, one in which there wasn’t explanation, in which things were what they are.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Then it happened?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes.

PASCALE — Clear is the word. Anyone who reads Alejandro’s books realizes that, despite the problems, he has a very strong ideal of love. He told me once that his conception of love was similar to that of mythology. I also had a very strong ideal of love. I lived with the promise, with the certainty, that I would experience a love story like this one. When we met, it was obvious right away. I’ve always been convinced that important things present themselves in a totally obvious and natural way. It’s like the artistic vocation: you don’t choose to be an artist. You are one or you’re not, it’s clear. Anyone can see that Alejandro is very strong, very fulfilled, and accomplished. The difference in our ages is, for me, a stabilizing factor. We never battle each other; we’re not rivals; we have an absolutely harmonious and complementary relationship. And I think that in a love relationship, you really have to have settled a lot of things. To feel well with the other person, you have to feel well with yourself.

OLIVIER ZAHM — Was it love at first sight?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Yes, it was incredible. Everything was written. It was strange, because I was reading the Tarot. I raised my head and I saw her.

PASCALE — It was like a movie.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — I was with another woman so, we waited a year without being lovers or anything. I wasn’t in a state to play out the secret and cheat.

PASCALE — He’s always dignified. I felt that we were connected beyond any kind of relationship based on seduction or age. There wasn’t any seduction. When I left the reading, I cried. I felt that he was passing something on that was very important. I was overwhelmed.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — Our lives changed. I’m immersed in emotional tranquility. I know we won’t have children, unless there’s a miracle. She’s a painter. I make drawings, she colors them, and we both sign them. They are our children. When you find the sacred relationship you still think women and men are beautiful, but you don’t have the desire to have other relationships. It’s not a moral choice, you’re just naturally full.

PASCALE — I really think that the key to sexual fulfillment is love, because with love there’s the trust and abandon which allows you to give deeply, whereas in the search for pleasure with many partners and experiences, you always stop midway. With love you go as far as possible, as high as possible. As a result, sexually, it’s wonderful, because everything comes together, everything is interwoven.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY — There’s the mythology of a relationship that goes beyond death. That’s why it becomes sacred, because you enter into the mythology.